But I, too, have ropes around my neck. I have them to this day, pulling me this way and that, East and West, the nooses tightening, commanding, choose, choose. I buck. I snort. I whinny. I rear. I kick. Ropes, I do not choose between you. Lassoes, lariats, I choose neither of you, and both. Do you hear? I refuse to choose.

– Salman Rushdie: East, West

Month: March 2014

Bringing a bit of India back home

In a recent piece of coursework, I was strangely asked to analyse a building near my University. As a literature student, I’ve always worked with texts; my head is always in a poem, play or a novel, yet this coursework was asking me to go out and explore, to carry out field work (how preposterous!). We had a choice of 5 buildings or so but we were allowed to look elsewhere, and, thinking about my experiences in India over the summer, I thought it would be interesting to examine Britain’s colonial past.

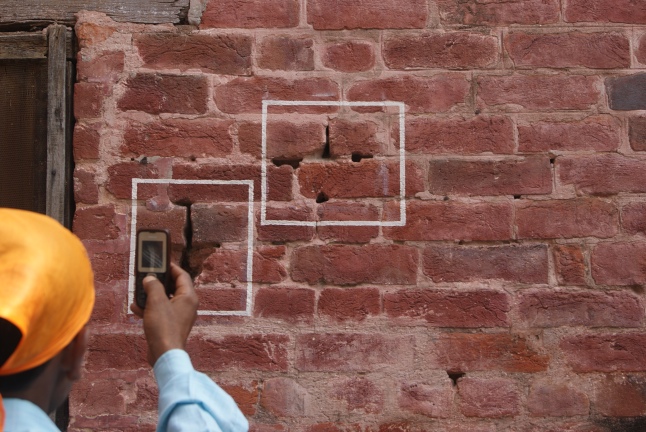

In Punjab, we visited a museum in Jallianwala Bagh which was a place made infamous by General Dyer who open-fired on a peaceful gathering in a large open space, killing many unarmed civilians. After this, anti-British sentiment became increasingly more pronounced, and the museum we visited there presented British Imperial rule in a largely negative light.

This got me thinking about the colonial relationship from the other perspective, and I was curious to see how India was represented as a colony in London.

Just as it happens, my university stands right opposite two very important reminders of colonialism – India House and Australia House – so I decided to walk to India House and see what kind of history could be read from this landmark. I feel no shame in reproducing my coursework here because the assessment was meant to take the form of a blog…so why not make real use of it? Click below for the pdf-document:

Without my trip to India I don’t think I would have enjoyed this coursework as much as I did. If I were learning about India House (or about India) from a textbook, without having first explored it and encountered the people there, I wouldn’t have had that direct involvement with the wider world around me. For this particular coursework, a solely theoretical approach would have made the process of learning much less engaging, and I’d doubt that what I had read about India House would really do justice to the experience of physically visiting it.

Gyanodaya, as I mentioned earlier, was all about seeing and feeling in order to really know anything. Travelling through India on a train gave me direct encounters with everyday people and their daily journeys, as well as the sights, smells and sounds of India. From this I have learnt that it is vital that emotional and subjective experiences should be made use of in the more traditional structures of academia.

In analysing India House my degree no longer seems like it is separate from my own personal history and experiences. My attitude to studying English Literature – a subject that I’ve always considered to be focused on minuscule detail and the ‘internal’ world of text and lofty ideas – has greatly been influenced by ‘College-on-Wheels’. Exploring what India meant to me prompted me to explore aspects of my home-city which I had taken for granted because encountered often. I now hope that the insights I’ve gained from my trip to India will continue to be made use of and help shape my academic work as it did here.

Odissi-Ballet fusion

I mentioned in my last post that dance was really important to the Delhi students and, gradually, it became important for me too through this cross-cultural experience. I also mentioned that I would post some images and videos later, so here they are!

The students of Delhi university organised a talent-show towards the end of the ‘College-on-Wheels’ trip in order to showcase different Indian dances for us Brits. The girl in the video and in the image on the left is my friend Roshnee performing an Odissi inspired dance (click here for an example – dancer starts at 1.17). Although a Delhite, her parents are originally from the state of Odisha (named Orissa previously), where this dance originates from. She gained admittance to Delhi University because of her advanced level of Odissi, much like how many US Institutions grant sport-scholarships. To me, this is a clear example of Dance’s central place in cultural and intellectual institutions in India.

In a ‘Whatsapp’ message, I asked her why she chose to focus on this dance form as opposed to any other and she responded by saying that she dances because it helps her remain connected or rooted to her family’s region, and is a response to Delhi’s ever-growing and ever-changing society. I thought this particularly interesting because, although the dance shown above is performed in the context of celebrating India’s heritage, it seems to also appreciate the interaction, or mixing, of styles and cultural practices that are not just from within India.

The male dancer is Roshnee’s friend, and he studies English Literature and is particularly keen on European dance styles. I think that the European and Classical Indian choreography works very well in the hybridity it displays. The dance doesn’t just highlight differences between a traditionally European dance style and a traditional Indian one, but emphasises similarities or synchronies that can exist between two supposedly very different art forms in the way the two dancers have coordinated their postures and movements. The dance showed me that although we often talk about the ‘homogenisation’ of culture which globalisation leads to there are cases where this sensationalised fear of a spreading ‘Western’ culture is ill-founded. Here, ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ traditions are working alongside each other, creating a new aesthetic – a new blend of culture – which is not just half- this and half- that (or ‘Westernised’ or ‘homogenised’) but an intertwined whole. Surely, the creation of new possibilities in cultural expression is a benefit of globalisation?

Finally, to give something back to the Indian students who had spent so long preparing the talent-show, the Edinburgh students we were travelling with rounded the evening off with this:

Even in Britain, dance and music seem to capture regional diversities, and both music and dance are being used in this video to express a cultural ‘uniqueness’ to ‘others’.

Punjab101: Dance and Nationalism at the Wagah Border

For anyone familiar with the innumerable cultural and racial stereotypes that exist today, India seems to be constructed by an overwhelming array of ‘iconic’ images such as yoga, spiritualism, its many religions and festivals, spicy foods, extreme poverty, the super rich, urbanisation and rapid population growth, the Taj Mahal, Gandhi, cricket, IT geeks, bindis and saris. My friends, too, often spontaneously list these features when imagining the country. However, this churning out of associations only fragments India beyond conceptualization. One only has to look at Slumdog Millionaire or Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom to see mainstream media’s tendency to depict extremes, and its ability to portray nations as distorted ‘others’.

It’s not only the media coming from the US or the UK, but the media within India that contributes to this, and, to a large extent, Bollywood also plays a crucial role in creating an exotic image of the country. With a hint of reluctance, I often have to deal with requests from friends here in London to show them ‘Indian dance moves’. Yet, what they are more often than not really referring to are Bollywood moves – seductive hip movements and head nods. Bollywood has become definitive of India’s aesthetic industry. Unfortunately, this is often at the expense of overwriting or appropriating classical and regional styles of dance and music. Bollywood is a very specific projection of a country and only one aspect of the many artistic practices and dance forms that represent India’s ancient heritage. It has come to dominate and capture the imagination of many though.

Below is a recent example of a typical dance routine and popular song which in English translates to ‘Come dance’:

However, in ‘College-on-wheels’ it became clear that dance was a major feature of youth culture in all its various styles, and Bollywood was not the sole source of inspiration or form of talent displayed throughout the week. The Delhi students were especially keen to celebrate their field trip ‘Punjabi style’ and not a single bus journey went by without our group dancing with teachers on India’s infamously risky roads. We were going to Punjab where a particular form of dance is a trademark of its strong regional ‘essence’. Bhangra is what I’m talking about, and as much as Bollywood has become representative of India in general, Bhangra is representative of the Punjab region in particular.

(KCL has a very good Bhangra team if I may say so myself – check it out if you don’t know what Bhangra is, and even if you do know what it is…check it out below anyway 😉 NB: it is adapted for the stage though)

Our first overnight train journey was to take us to Amritsar and I found it especially unsettling. Reeking of sweat like I’ve never reeked before, feet swollen, mosquito bites and carrying a heavy suitcase as well as TWO laptops given to us in our group of four, getting used to travelling on a humid train which chimes – no, chimes is too delicate a word to describe the trauma of being woken up at 3 a.m – a train that screeches intermittently throughout the night was no easy feat. However, our arrival in Amritsar was the highlight of the trip for me because it was the start of my integration with the Delhi students which compensated for the train journey. How did this occur? Through dance, of course. At the iconic Waghah border – the border between India and Pakistan, where nationalist feeling runs high – dance and music drew us all in, irrespective of our nationality.

We arrived at around 4pm but had to wait until sunset for the actual show-off between the Pakistani Rangers and the Indian Border Security Force. In the meantime, the Indian side of the border exerted its energies into making us chant ‘HINDUSTAN ZINDABAD’ (Long live India) whilst playing patriotic songs and encouraging different parts of the audience to shout the loudest. Whistles, drums, half a dozen Indian flags being passed through the crowd, clapping, jeering, and, of course, Bhangra surrounded me and for the first time since arriving in India I found myself admist the boys who were partying down like there’s no tomorrow (we had been kept separate for pastoral purposes). Thrown into this eclectic environment, I was exhilarated by the display of national pride – something which is only pompously shown in England on occasions such as the Olympics, Jubilee and the Royal Wedding. Music and dance made sentiment reach fever pitch and patriotism was infectious. I was drawn into chanting ‘Hindustan Zindabad!’ and ‘Jai Hind’ with a quick suppression of guilt that I was officially a British citizen.

Speaking to many students after the military display, they said they preferred to dance Bhangra rather than typical Bollywood moves because Bhangra was ‘true’ to the Indian spirit whilst Bollywood had become more ‘Westernised’. The strong presence of music and Bhangra at the Wagah Border, which celebrates being ‘Indian’ (or being ‘Pakistani’ if you are on the other side), helped to convert the tension between the two countries into something communal and light-hearted. Indian nationalism was something which I had never come across, (apart from in cricket matches), and the interplay between Punjabi Bhangra and nationalist celebration showed me how essential this regional dance is in understanding the Indian students’ affiliation to their country.

Punjab felt the partition of India most violently as many riots broke out when it was divided in two. Parts of it fell into the newly created Pakistan and families and religious groups were separated. Its regional dance, then, may compensate for the separation of communities by bringing people together, which I witnessed at the Wagah Border. Pakistan was just as lively as India, and, rather than emphasising perceived differences, the choreographed military rivalry on both sides only seemed to highlight similarities between the nations – that they can work together for a shared purpose. I realised that they were both using art forms to broadcast an image of their respective countries and cultures (and to show their military power), but, ironically, this image was of cooperative unity rather than separation. This gave me a new perspective on Indo-Pakistani relations.

To summarise this rather long post, I can say that dance is prominent everywhere in India. From Bollywood to Bhangra, Garba (Gujarat’s dance) to Odissi (Orissa’s) and even Disco and hip-hop, many forms of dance were represented on the trip, with some more strongly associated with ideas of authenticity and tradition than others. At the Wagah Border I saw how the Delhi students really valued their diverse ancestry from India’s different states and I’ll try and find a recording of their student performances in Punjab to show you how important dance and music are to the young people of India.

I hope you’ll remember this post next time you think Bollywood to be indicative of India’s cultural output, and that there is much more too it than just entertainment!

These images are a flavour of my experience at the Wagah border: